The accounts of the death and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth, as detailed in the New Testament, occur within the historical context of first-century Jerusalem. The New Testament writers consistently maintain that Jesus lived, died, and was witnessed alive post-resurrection. The apostles were mindful of potential skepticism and emphasized the reliability of their eyewitness testimony. The Apostle John highlights the standards of Greco-Roman legal evidence, stating, “That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we looked upon and have touched with our hands, concerning the word of life” (1 John 1:1, ESV). Similarly, Peter underscores the credibility of eyewitness testimony: “We did not follow cleverly devised myths... but we were eyewitnesses of his majesty” (2 Peter 1:16, ESV).

To reinforce the historical authenticity of these claims, the following archaeological and textual evidences are presented chronologically:

10. Garden and Cave of Gethsemane

Jesus prayed in Gethsemane (Matthew 26:36), which aligns with an ancient olive grove near the Mount of Olives today. Archaeological findings support that a cave in this location was historically utilized for olive pressing, corresponding with biblical descriptions.¹

9. Caiaphas Ossuary

A first-century ossuary inscribed “Joseph son of Caiaphas” discovered in Jerusalem likely belonged to Caiaphas, the high priest who oversaw Jesus' trial, aligning with biblical accounts and historical texts.²

8. Pilate Stone

A limestone inscription discovered at Caesarea Maritima explicitly references “Pontius Pilate, Prefect of Judea,” confirming the biblical portrayal of Pilate’s historical role and presence.³

The Pilate Stone in the Israel Museum Jerusalem.

7. Praetorium

Herod’s palace is identified as the governor’s headquarters (Praetorium), where Pontius Pilate tried Jesus. Archaeological excavations beneath Jerusalem's Tower of David Museum substantiate this identification.⁴

This model of Herod’s Palace is on display at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Many scholars believe there was a public courtyard next to the palace where people could gather without entering the palace precincts. This is the basis for the colonnaded square in the model that is accessed by the gate seen in the middle of the photo. This was likely the place where Pilate sat on the judgment seat and addressed the crowds.

6. Heel Bone of a Crucified Man

The discovery of a first-century crucifixion victim’s heel bone in Jerusalem provides tangible evidence of Roman crucifixion practices contemporary to Jesus' time, reinforcing the biblical narrative of crucifixion.⁵

5. Alexamenos Graffito

The Alexamenos Graffito is a blasphemous archaeological find relating to the crucifixion of Jesus. In 1857 a drawing was found scratched in the plaster on one of the walls in a structure near the Palatine Hill in Rome. It depicts a man with a donkey’s head on a cross and a person in front raising his hand. The accompanying inscription reads, “Alexamenos worships [his] god.” [“Alexamenos Graffito,” University of Chicago.] https://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/gladiators/graffito.html

It appears to be graffiti intended to mock a Christian named Alexamenos. Why a donkey’s head? The origin of the idea Christian’s worshiping a donkey-headed God is unknown, but Tertullian notes that even in his day some were “under the delusion that our god is an ass’s head.” This is the earliest artistic depiction of Jesus on the cross, and while it is disrespectful, it is early archaeological evidence that people worshiped the crucified Christ as God.⁶

The Alexamenos Graffito depicts Jesus on the cross with the head of a donkey and a man named Alexamenos worshiping him.

4. Shroud of Turin

Scientific studies, including recent Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering, have dated the Shroud of Turin to the first century. While not conclusively Jesus’ burial shroud, it aligns remarkably with gospel descriptions of crucifixion practices.⁷

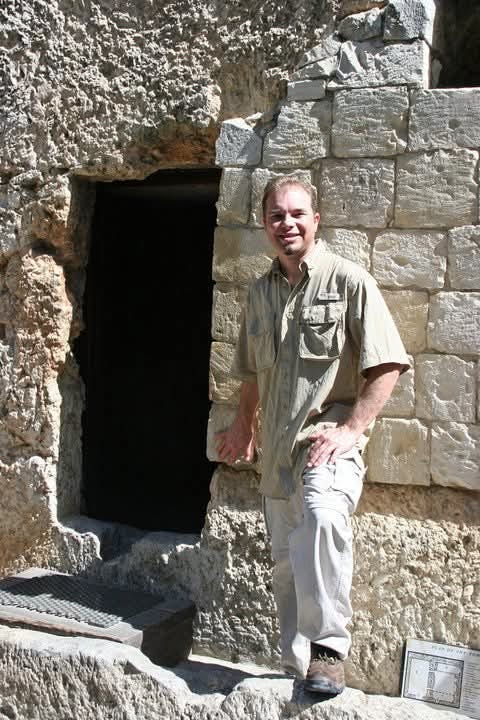

3. Church of the Holy Sepulchre

Archaeological and historical investigations strongly support the Church of the Holy Sepulchre as the authentic site of Jesus’ burial. Constantine’s fourth-century identification and subsequent discoveries provide credible affirmation.⁸

2. Nazareth Inscription

An imperial edict, likely issued by Emperor Claudius, warns against tomb desecration, seemingly responding directly to early Christian claims regarding Jesus' resurrection. This artifact indicates early imperial awareness and concern over the empty tomb narrative.⁹

The Nazareth Inscription – a first-century Imperial edict pronouncing the death penalty for anyone caught stealing bodies from tombs.

1. Manuscript Evidence

Numerous manuscripts and early writings, including papyri (e.g., P66), testimonies from early Church Fathers (e.g., Clement, Ignatius), and accounts by historians such as Josephus and Tacitus, collectively affirm the historical credibility of Jesus' resurrection.¹⁰

Together, these archaeological and textual evidences robustly support the historical reliability of the gospel accounts regarding Jesus' death and resurrection, providing substantial foundations for the Christian faith.

This fragment of Papyrus P66 (second or third century) contains John 20:27-31, making it the oldest surviving gospel manuscript testimony of the resurrected Jesus.

In addition to the biblical gospels, other Christian writers, some of whom learned of the death and resurrection of Jesus directly from the apostles, testified that Jesus lived, died, and rose again. These include: Clement of Rome (ca. AD 70-96), Ignatius (ca. AD 11), Polycarp (ca. AD 110-140), and Quadratus (ca. AD 115-138).

Finally, two non-Christian ancient historians also noted the death and reported resurrection of Jesus. Josephus (ca. AD 93), wrote a famous passage that, in its Greek form, was altered by a Christian scribe in a way that all scholars – Christian and non-Christian – acknowledge includes elements that a Jew like Josephus would never have written. However, an Arabic form without these pro-Christian additions was discovered in the 1970’s. It reads:

At this time there was a wise man who was called Jesus. His conduct was good, and [he] was known to be virtuous. And many people from among the Jews and the other nations became his disciples. Pilate condemned him to be crucified and to die. But those who had become his disciples did not abandon his discipleship. They reported that he had appeared to them three days after his crucifixion, and that he was alive” [Schlomo Pines, An Arabic Version of the Testimonium Flavianum and it’s Implications. (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1971), 9-10.]

Tacitus (ca. AD 116) wrote about Nero’s attempt to deflect blame onto Christians when he was accused of starting the Great Fire of Rome:

“Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judæa, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome” [Tacitus, Annals, 15:44.]

The “most mischievous superstition” is likely a veiled reference to the belief of the early disciples that Jesus had risen from the dead.

NON-CHRISTIAN HISTORIANS DOCUMENTED THE DARKNESS OF THE EARTH DURING THE CRUCIFIXION

Three of the four gospel accounts (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) document the three-hour darkness during Christ's crucifixion (Matthew 27:45, Mark 15:33, Luke 23:44–45). This event is corroborated by four non-Christian eyewitness testimonies.

Thallus wrote a history of the eastern Mediterranean world since the Trojan War. He wrote his regional history in about AD 52. Although his original writings have been lost, he is specifically quoted by Julius Africanus, a renowned third century historian. Thallus, writing around AD 52, attempted to explain this darkness as a solar eclipse, a claim referenced by Julius Africanus. Phlegon, a Greek historian, wrote an extensive chronology around AD 137 and recorded this darkness as occurring in AD 33, accompanied by an earthquake.¹² Julius Africanus¹¹ composed a five volume History of the World around AD 221. He argued against the eclipse explanation, noting the impossibility of an eclipse during a full moon lunar cycle of the Passover and linking the darkness explicitly to the crucifixion event.¹³ He also questions the link between an eclipse, an earthquake, and the miraculous events recorded in Matthew’s Gospel. Eclipses do not set off earthquakes and bodily resurrections. We also know that eclipses only last for several minutes, not three hours. For Africanus, naturalistic explanations for the darkness at the crucifixion were grossly insufficient, as he showed by applying real science. Africanus would later in life convert to Christianity. His historical scholarship so impressed Roman Emperor Alexander Severus that Africanus was entrusted with the official responsibility of building the Emperor’s library at the Pantheon in Rome. Tertullian, the famous second century apologist, also hails the darkness as a ‘cosmic’ or ‘world event’. Appealing to skeptics, he wrote:

“At the moment of Christ’s death, the light departed from the sun, and the land was darkened at noon-day, which wonder is related in your own annals, and is preserved in your archives to this day.” 14

The Bible does not suggest that this darkness was confined to Jerusalem alone, but rather extended across the earth. The accounts of this unusual darkness that came over the earth were documented by four historians from different geographical locations. Thallus resided in Rome, Phlegon lived in Tralles (modern-day Turkey), Sextus Julius Africanus resided in Emmaus, in Palestine, and Tertullian lived in Carthage, located in what is now Tunisia.

We have an extensive array of extremely early, historically reliable, and highly respected sources for the darkness that covered the land during the crucifixion. The list of Matthew, Mark, Luke, Thallus, Phlegon, Africanus, and Tertullian. The darkness at the crucifixion was a real, documented historical event, supported by multiple geographically diverse historical sources.

Footnotes:

¹ Joan E. Tayler, “The Garden of Gethsemane: Not the Place of Jesus’ Arrest.” Biblical Archaeology Review, July/August 1995.

² Josephus, Antiquities, 18.2.2; Fant & Reddish, 2008.

³ Clyde E. Fant and Mitchell G. Reddish, Lost Treasures Of The Bible, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids Michigan, 2008, p. 316.

⁴ Shimon Gibson, The Final Days of Jesus: The Archaeological Evidence, (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2009), p. 91.

⁵ John J. Davis, “Rethinking The Crucified Man From Giv’at Ha-Mivtar.” Bible and Spade. Vol. 15. No. 4 (Fall 2002).

⁶ Tertullian, Apology XVI.

⁷ De Caro, L.; Sibillano, T.; Lassandro, R.; Giannini, C.; Fanti, G. X-ray Dating of a Turin Shroud’s Linen Sample. Heritage 2022, 5, 860–870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ heritage5020047

⁸ Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, “The Argument for the Holy Sepulchre,” Revue Biblique. Vol. 117, No. 1 (JANVIER 2010), 63-64.

⁹ Clyde E. Billington, “The Nazareth Inscription: Proof of the Resurrection of Christ?” Associates for Biblical Research.

¹⁰ Jonathan Bernier, Rethinking the Dates of the New Testament. (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2022), 275., Pines, 1971; Tacitus, Annals, 15:44.

¹¹ Julius Africanus, History of the World.

¹² Phlegon, Chronography.

¹³ Julius Africanus, History of the World.

¹⁴ Tertullian, Apology.

Other References:

Clement, Epistle of 1 Clement, 21:6; 24:1.

Ignatius, Epistle to the Smyrnaeans, 1 and 2.

Polycarp, Epistle of Polycarp, 1:2.

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, 4.3.2.

Tacitus, Annals, 15:44.